Three-hundred years ago, in a city not so far away…

A few documents have survived from the days surrounding the premiere of the “Johannes-Passion”, all of which paint a rich picture of Bach and his involvement in the musical life of the city outside of his composition studio. His duties in Leipzig as cantor and music director were multifarious – as cantor and music director, they included the contribution of new religious music for the four churches, its performance, the development of young musicians who performed his music, and the supervision of all matters surrounding this enterprise. The story behind the 1724 performance of the “Passion” crystallises the nature of his professional life. Bach expected to present this work, his first major contribution to church music in Leipzig, at the Thomaskirche and had booklets printed (most likely with the text of the “Passion”) with this in mind. The city, however, intended it to be performed at the Nikolaikirche. This mishap eventually landed Bach in the office of the Superintendent, where he was reprimanded. Although he is said to have accepted fault for this, he demanded to have the harpsichord of the new venue repaired and the choir gallery enlarged, two expenses that complimented the city’s printing of flyers announcing the change of venue.

We tend to romanticise a vision of Bach the genius, perhaps inherited from mainstream scholarship and aesthetic critiques of the past two centuries, churning out masterpieces that reflected the perfection of his cerebral transcendence, far removed from the banalities of our material reality. Such anecdotes, however, encourages a richer understanding of Bach, the man and “craftsman”, which in turn leave us in awe in regards to the sheer indefatigability of his inventiveness and the industry with which he committed this to actual notes on the page, and in performance. Furthermore, he was an individual who balanced his artistry with the intense interpersonal interactions his position demanded. He was expected to be not only a musician, but also a well-organised and constructive ally of the clergy, and an inspiring and magnanimous mentor to the boys he was expected to train musically, not to mention his many children and his rich family life. How could one man accomplish so much? Clearly, he was not alone.

Introduction (Tetsu Isaji)

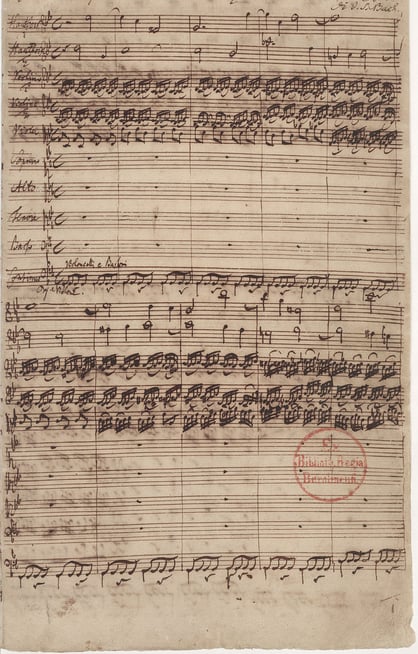

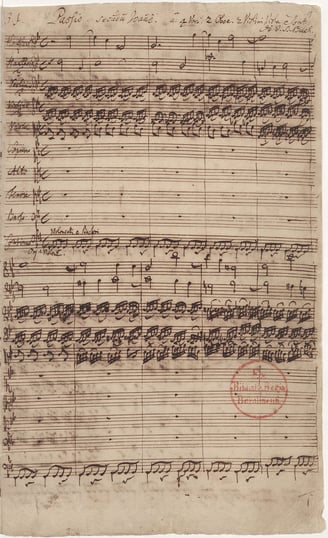

First page of autograph manuscript

The surviving manuscripts of the “Johannes-Passion” show that the preparations for its performance, like that of many other works, involved many hands – manuscripts were prepared by his most advanced students or his own wife and children, and performances required the tireless work of diligent instrumentalists and organisers. Even the preparation of a service booklet alone called for serious coordination and attentiveness, both from Bach and his team as well as the clergy. The realisation of such a musical event, therefore, was a city-wide endeavour: it may not be too far-fetched to say that the city itself became a sort of “instrument” in the face of such a large undertaking. In this sense, Bach’s music sounds today partly because of those who inspired and sustained his work, and those who worked to protect it for posterity. The imprints of the many forces and energies that flowed around him, embodied by the notes on the page, compel us to seek enlightenment through the act of appreciating and playing them.

Bach based the “Passion” on the gospel of John, and several textual sources from contemporaneous writers. His music, in this light, can be framed as illustrations of this intertextual basis. The movements of the work can be divided into three categories: the choruses (involving all musicians) and recitatives (solo singers, called “evangelists” accompanied by a small troupe of instrumentalists) based on the gospel, and arias and chorales based on poetry. The latter category functions as a sort of illustration of the points mentioned in the former, offering rich musical reflections on the story told by the recitatives and choruses. For those of you who are new to these terms, the first few movements might serve as a reference – the first movement (No. 1, involving all musicians), is a chorus, the second movement (2a-e) opens with a recitative which is quickly interrupted by a chorus (listen out for the phrase “Jesu von Nazareth”) and then concluded with another recitative, and the third movement (No. 3) is a chorale, involving four vocal parts (soprano, alto, tenor, and bass) accompanied by instruments and four beats per bar. No. 7 may take you by surprise. Unlike a recitative, its metre is regular, and there are fewer musicians involved than in a chorus or a chorale – this is an aria. If one is lost while following the text, listen out for the first words of each movement. A couple of exceptions are worth noting: movements No. 24 and 32, respectively, combine the aria and chorale, and aria and chorus, creating an even richer musical effect. One is often left amazed by the creativity with which Bach illustrated the story of the crucifixion, which must have elicited an extremely strong response in the public back then as it does today.

The “Johannes-Passion” and its elements

Brussels is a fantastic city to meet young allies who share a passion for music of the past. With the two conservatories and their beautiful early-music departments, we were blessed to have this opportunity to put together our very own “Johannes-Passion”. Singers and instrumentalists united in small rooms throughout the city for hours at a time, experimenting with all kinds of approaches to making the work come alive, and its text as clear as we could realise it. An afternoon during Easter 2023 in a small bedroom in the outskirts of Brussels with just one harpsichord and a general score of the “Passion” led to a series of WhatsApp invitations to friends and colleagues asking them to read the work together. Little by little, we began to chip away at a work that was at once familiar but also wholly new to most of us, who had yet to perform the “Passion”. By assembling the work from the ground up, we realised how little we knew about Bach and this work, and that there are still many mysteries surrounding its performance practice and the score itself. Luckily, we were not alone.

First and foremost, we are truly grateful to Église Notre-Dame des Victoires au Sablon, its conseil d’administration, and the titular organists including Benoît Mernier, who kindly offered us an exquisite venue for tonight’s event. We would also like to thank our mentors at the conservatoires and beyond who offered invaluable advice and support. Special thanks is also reserved for the Hoofdstedelijke Kunstacademie who allowed us to rehearse in their facilities. Furthermore, we thank the harpsichord-builder Bastian Neelen, who kindly completed and loaned us his beautiful copy of a Hamburgian harpsichord from 1720 just for this project. We also extend our thanks to the members of KASK’s instrument-making department, who supported Bas during this period. We are beyond indebted to Sigiswald Kuijken, who not only shared with us his secrets for the initial preparation of a work of this magnitude but also offered to jump in to help us during the final days of the project. I first met this extraordinary individual during a project organised by the early-music department of the conservatoire, who then invited me to prepare his harpsichord for a concert in exchange for some lessons. The “Passion” was the only thing on my mind and, in a way, it is one of the most opportune springboards for anyone’s musical development – we are all blessed to have the opportunity to follow his wisdom. Finally, we thank all of you for coming out to share this moment with us – let us, together, make the “Johannes-Passion” resound for the next three-hundred years to come.